Reading Georgette Heyer: These Old Shades

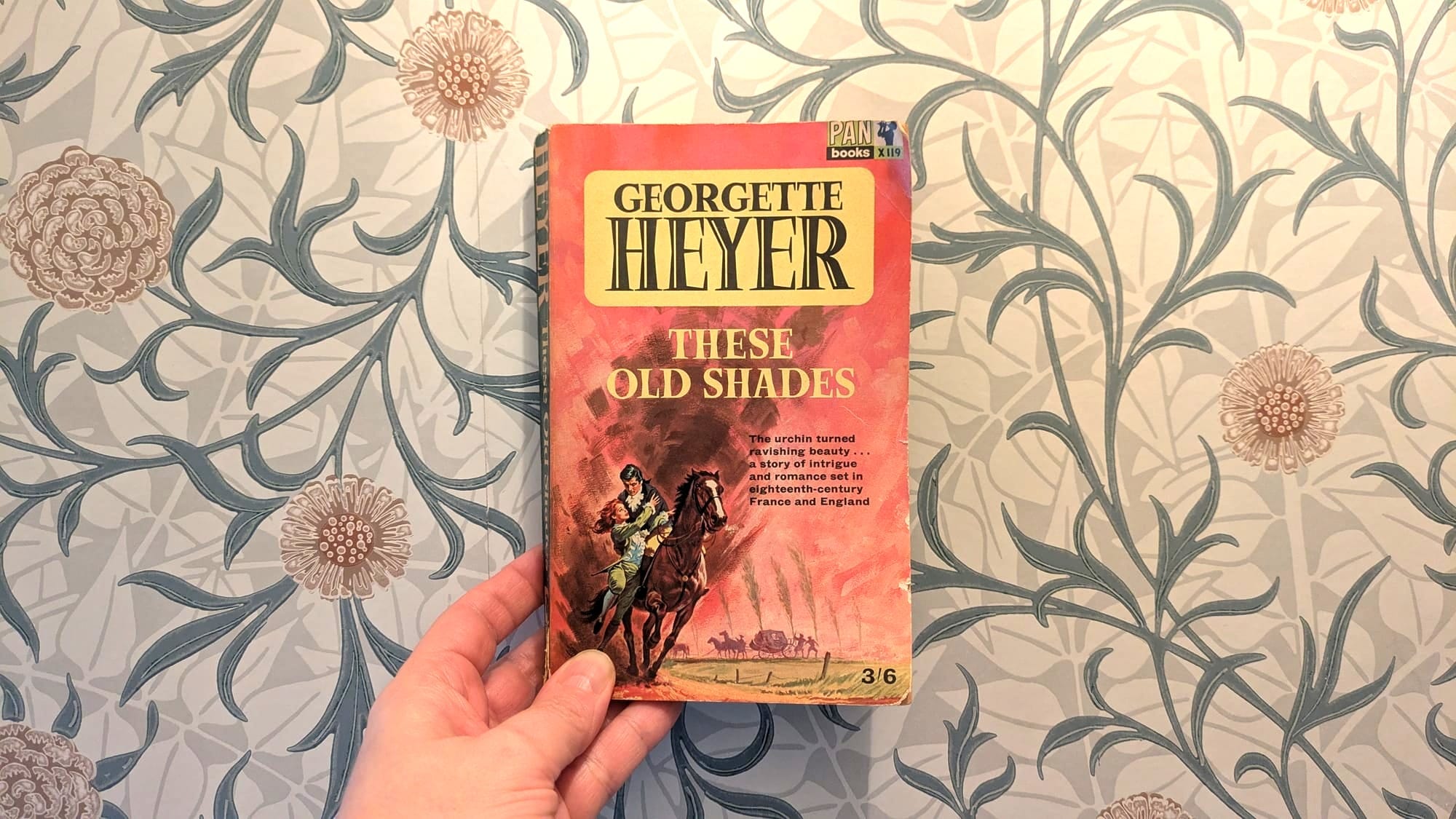

I finished Georgette Heyer's debut novel, The Black Moth, wishing that I could read more about the intriguing, unusual character at its centre — Tracy Belmanoir, Duke of Andover, better known as "Devil". A small amount of research revealed that I could do just that by jumping forward in her bibliography to her sixth published novel, These Old Shades from 1926. I couldn't resist.

Heyer began writing this book in 1922 and intended it to be a more action-packed continuation of the 1750s world she had covered in her debut. However, she ended up putting it aside for a few years — publishing novels about other historical periods like The Great Roxhythe and Simon the Coldheart in the interim — and only picked it back up again in 1925, battling to complete it for publication in the difficult weeks after her father died. It's not a conventional sequel. Rather, it reworks Devil and a few of the minor characters into a new versions in a new story. Her title, These Old Shades, is a quotation from a poem and a nice little nod to the reader who might recognise her old characters in their new guises.

Her shadowy villain becomes Justin Alastair, Duke of Avon, an English aristocrat living in France who is now enjoying a period of prosperity after earlier gambling losses. He still has a reputation for coldness and dissolute behaviour, but his edges have been softened. There is light in his eyes now; he has a studied boredom about him, yet he's not the nihilist of the earlier book. To corrupt a phrase, in The Black Moth, we see a "Devil without a cause", who can bring himself to care for nothing. By contrast, "Satanas", as Justin is sometimes called, has passion and an object in life. Even if his "cause" is to revenge himself on a French aristocrat, the Comte de Saint-Vire, who twenty years earlier refused Justin permission to marry his sister. All of which is to say, while this version is still dark, he isn't abducting debutantes just to feel something any more.

The instrument of his revenge literally bumps into Justin in the opening chapter of These Old Shades. A poor young lad named Léon collides with him on the mean streets of Paris while trying to avoid a beating. Seemingly on a whim, Justin uses his diamond tie pin to buy Léon from his older brother — a grim transaction involving a human life — and takes the child home to become his page. Léon is pathetically grateful and declares his undying loyalty and obedience to his new master. Justin seems to find this rather droll. Over the next few nights he parades his new red-headed, base-born page through all of the fashionable establishments of Paris, to the general amusement of his social circle.

Of course, Satanas has a scheme afoot. He has discerned at a glance that Léon is really Léonie, a girl of twenty who for some as-yet unknown reason has been living and working at her brother's tavern in disguise as a much younger boy. Her red hair and black eyebrows instantly remind Justin of his enemy, the Comte de Saint-Vire. He can also apparently tell that she is no tavern-keeper's sister and by rights belongs to a much higher social class. All signs point to her being a wonderful way of embarrassing Saint-Vire and repaying him for the humiliation he visited upon Justin all those years ago. It works from the start: Léon causes quite a stir following Justin around Paris, including at Versailles. His enemy is provoked.

From here, Heyer keeps ramping up the drama. Léon is informed that she must be Léonie full-time now, a prospect that fills her with horror. Justin takes her to England to stay with his sister and aunt — propriety demands that she can't follow him around town now that she's officially a girl — and we are treated to a makeover montage worth of a late nineties romcom. There's plenty of humour in Léonie's reactions to women's fashions. She is very against having to wear skirts. Then Léonie is abducted by the Comte, drugged and smuggled back to France (she, hilariously, dubs her captor a "pig-person" and refers to him this way for the rest of the book). Heyer breaks with the conventions of sensational fiction, though, and has Léonie mastermind her own escape, rather than showing her as a helpless female who needs a male character's aid. She rides to safety with Rupert, Justin's younger brother, having already extricated herself from the Comte's clutches by the time he arrives. She's no damsel in distress.

Rupert's horse, by the way, has a lovely comic subplot of its own. He effectively steals it from a blacksmith's in his haste to chase down Léonie and is then pursued himself for several chapters by the horse's rightful owner, a middle-class merchant, who just doesn't think that aristocratic derring-do is a good enough reason for him to be both missing a horse and out of pocket. It undercuts some of the more melodramatic stuff wonderfully.

Because the melodrama is not in short supply in the second half of this book. Justin's scheme leads up to a grand denouement in which he monologues for several pages, gradually leading the assembled society worthies towards an understanding of Léonie's true identity. A gun is produced, someone shoots themselves right there in the salon, and Justin just laughs maniacally through the chaos of it all. There's still a touch of the old Devil about him, for sure.

But unlike the original Devil, Justin does also enjoy life on the way to this bloody finale. The chapters that deal with Léonie's introduction into Parisian society and all the different fashions everybody wears are wonderfully light-hearted and entertaining. The historical moment is rendered in much more detail in this book and the cameos by real-life figures such as Louis XV and La Pompadour are a good addition. There's a real Cinderella feel about this aspect of the novel, with Justin's sister Fanny playing the role of Léonie's fairy godmother. Rescued from her humble station and decked out in the finest silks and stains, she does indeed go to the ball.

The cross dressing aspect of the plot requires the reader to trust that Heyer can bring it all to a satisfactory conclusion in the end. Which she does, even though for the first two-thirds of the book, it's simply ridiculous that nobody apart from Justin has noticed or remarked on the fact that poor naive little "Léon" is really a woman of twenty wearing trousers. Sorry, breeches. I wondered if it might have been a little easier to read if Heyer had dropped a few hints that people had noticed, but were too polite or too curious to mention it. Léonie herself is also a bit implausible as a character, a confusing bundle of innocence and wisdom who seems to shift about in maturity as the plot demands. She's great fun throughout, though, so I forgive her.

Keen-eyed readers will have noticed that I haven't mentioned the romance element of this book at all. There is one, and it is the Cinderella moment that you might expect. It just wasn't very interesting to me. I was far more focused on the kidnappings and the witticisms. I know that Heyer is famous for her romantic fiction but I don't feel like I've read her at her best in this arena yet. I have that still to look forward to! That aside, this was a very enjoyable novel and I completely understand why it became an early success that solidified Heyer's reputation as a truly popular novelist.

Three Other Thoughts

- I found it refreshing that Léonie, post-makeover montage, is continually begging to be allowed to be Léon again. She's sarcastic about it, too: "Monseigneur, do you understand what it is to be put into petticoats?". As much as she seems to enjoy rendering everyone speechless by appearing at a ball in a silver evening gown, for day to day life, she prefers breeches and being allowed to say exactly what she thinks. Who wouldn't? I feel like cross-dressing heroines in historical romances are usually shown to be more grateful for being "rescued" from the horror of having to wear trousers.

- Early on in the book, Justin crushes a gold snuff box in his bare hands to show just how much he hates someone. Exemplary character work: we immediately know that he's melodramatic and rich.

- The book is predicated on some pretty rigid class assumptions — Léonie is "obviously" too good to be the daughter of a farmer and must therefore be of noble birth. I have no doubt that this was representative of attitudes in the 1750s and it reminded me of how flexible modern historical fiction has become with this sort of thing.

My Favourite Phrases

This is going to become a regular feature, I can tell. Susan, a commenter on my post about The Black Moth, has directed me to one of Heyer's slang sources, Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue by Francis Grose from 1811, and I'm having a wonderful time perusing it. Here are my highlights from These Old Shades:

- Justin is "always a damned smooth-tongued icicle", according to a close friend.

- "Avon swept the lady a magnificent leg" — I still love this phrase!

- Someone is "seated mumchance", which from research I think means sitting silently.

- Once Léon has become Léonie, she and Justin discuss which slang she is allowed to use now that she's a girl. He insists that she is not, under any circumstances, to say "lawks" or "tare an' ouns". The only permissible exclamations are "'pon rep" and "Lud!". It is not explained why these are more suitable for women.

Thanks for reading. I'm making making way through Georgette Heyer's historical novels — you can find all the entries so far here.

You can support my work with a recurring contribution or leave a one-off tip.

Member discussion