Reading A Lot, But Differently

I stopped being able to finish books in 2020, about two weeks into the first Covid lockdown. The problem did not go away for years. I forced myself to read for work, but for pleasure skipped from volume to volume, sometimes only perusing a few pages before throwing another one on the reject pile. I wrote about this at the end of 2022, describing what it felt like to lose the ability to read at length, which until then had been for me "as unconscious as breathing".

This was my assessment as to why I could not get to the end of a narrative:

"I think what makes me put a book down and lose all desire to ever pick it up again is a feeling that I should be doing something more worthwhile with my time. Something that will make things better. I cannot articulate what that other activity is, nor have I, in six months of listlessly turning pages, chanced across it. I just know that reading that book, in that moment, is not it."

Last year, 2024, was the first time since then that I could finish books consistently again. A few factors contributed to that:

- Therapy, via which I gained a better understanding of how long I had existed in fight-or-flight mode, tethered to my phone because I expected to receive an emergency call every moment.

- Publishing my own book, marking the completion of a writing project that had preoccupied me since 2017.

- Finally fully accepting the idea that all reading is reading, whether the book is in the form of an audiobook or is (or is not) from a particular genre.

- Planning, tracking and reviewing my reading properly for the first time.

It's this last point that I'm focusing on today.

Read on for:

- My stats for the year, with reflections and analysis.

- Recommendations for the best books I read.

- Thoughts about what I'm changing for 2025.

2024 in Review

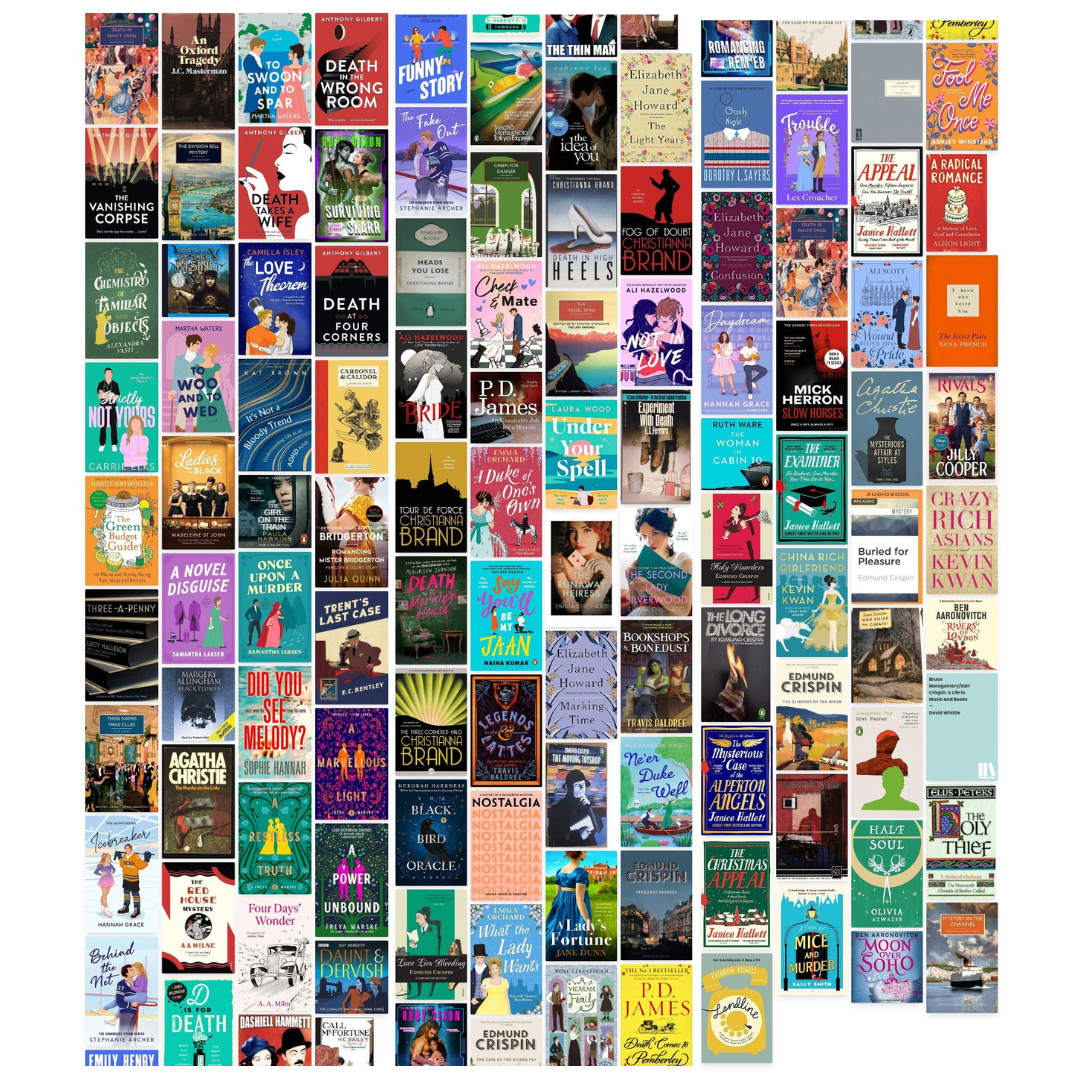

- I read 112 books in 2024. See them all here. My goal was 104, or two a week, so I exceeded that comfortably. I started writing monthly reading round-ups in September, so you can get more details of what I read in the last third of the year here.

- 106 were fiction and 6 were non-fiction.

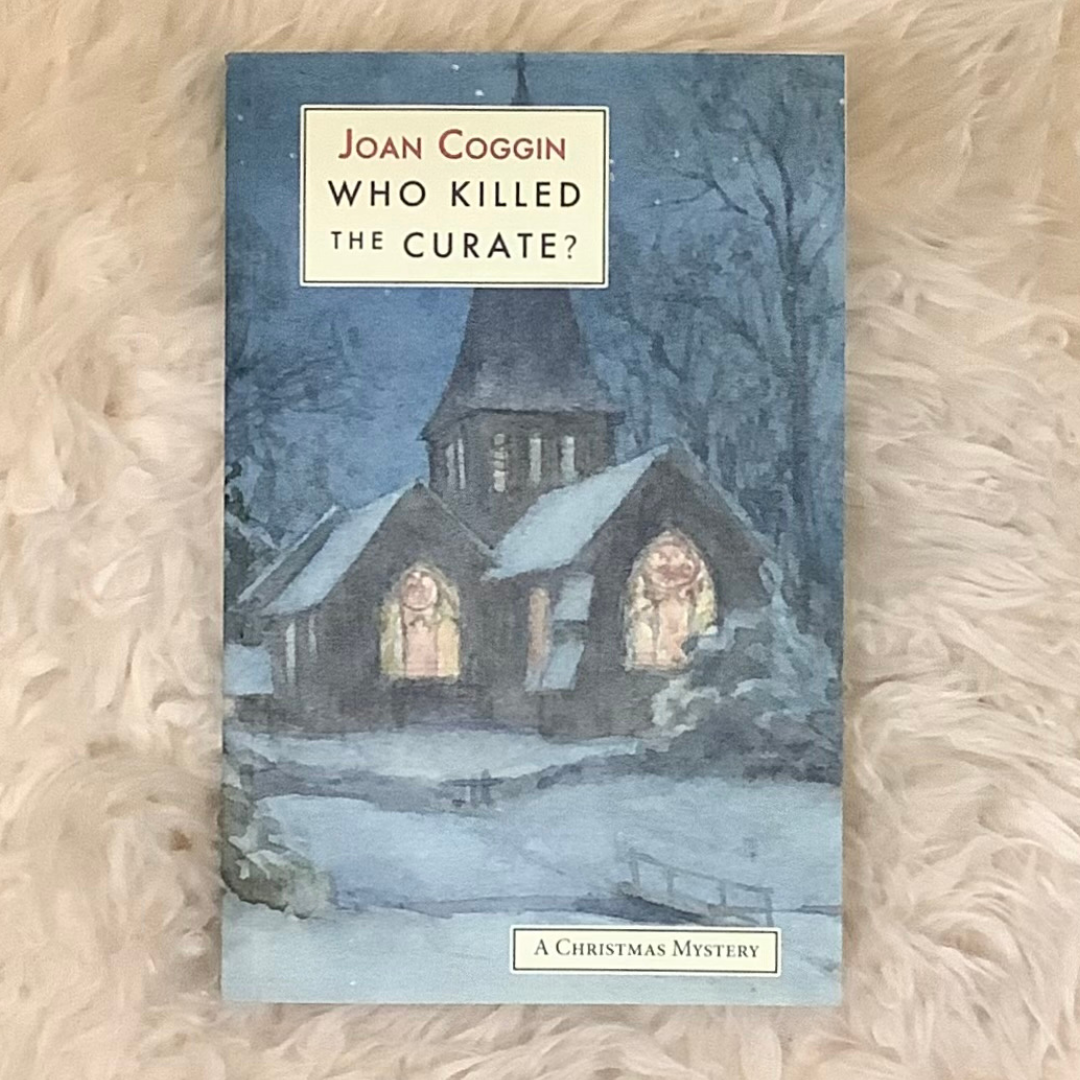

- My most-read genre was (unsurprisingly!) crime. The second was romance, followed in a distant third by fantasy.

- My three most read authors were:

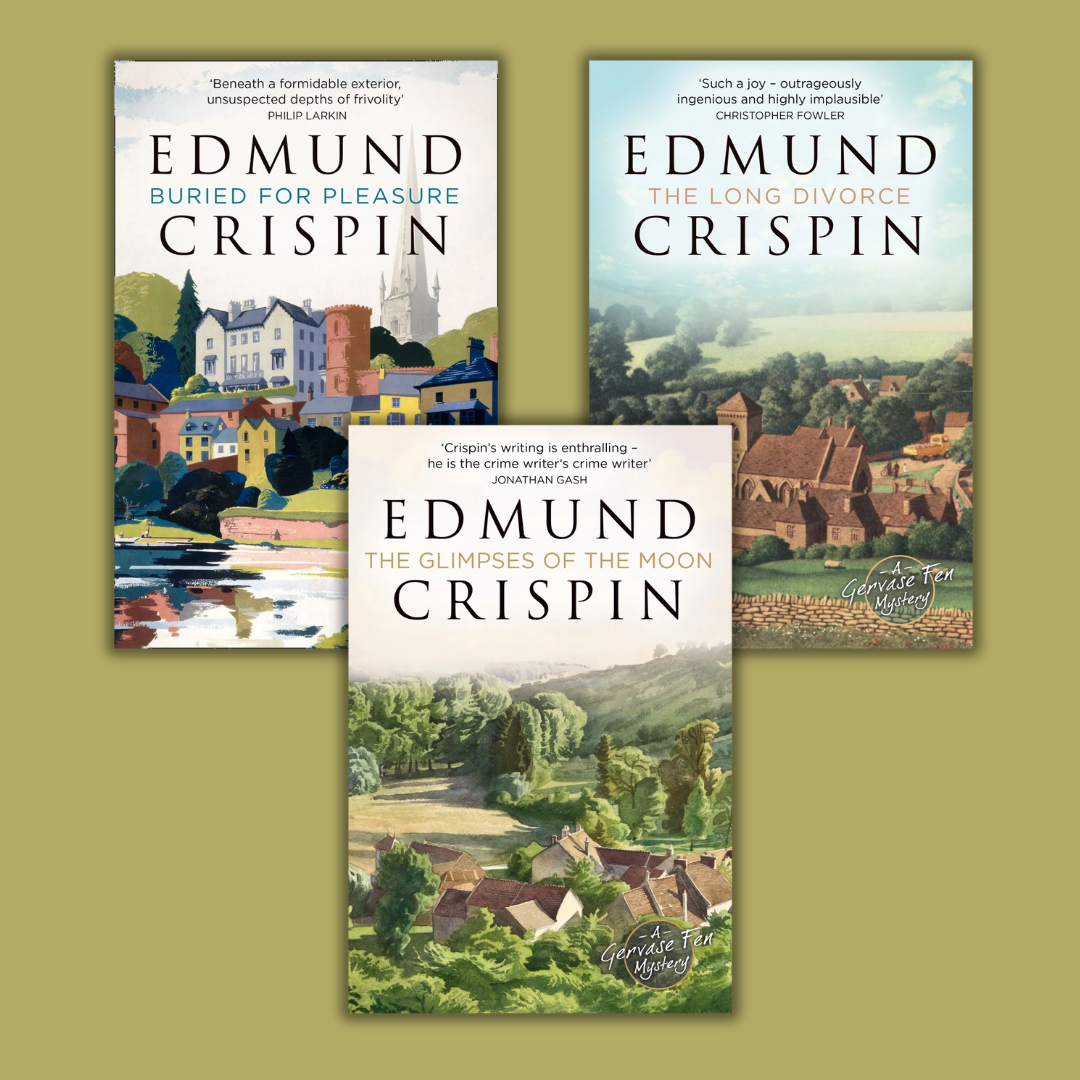

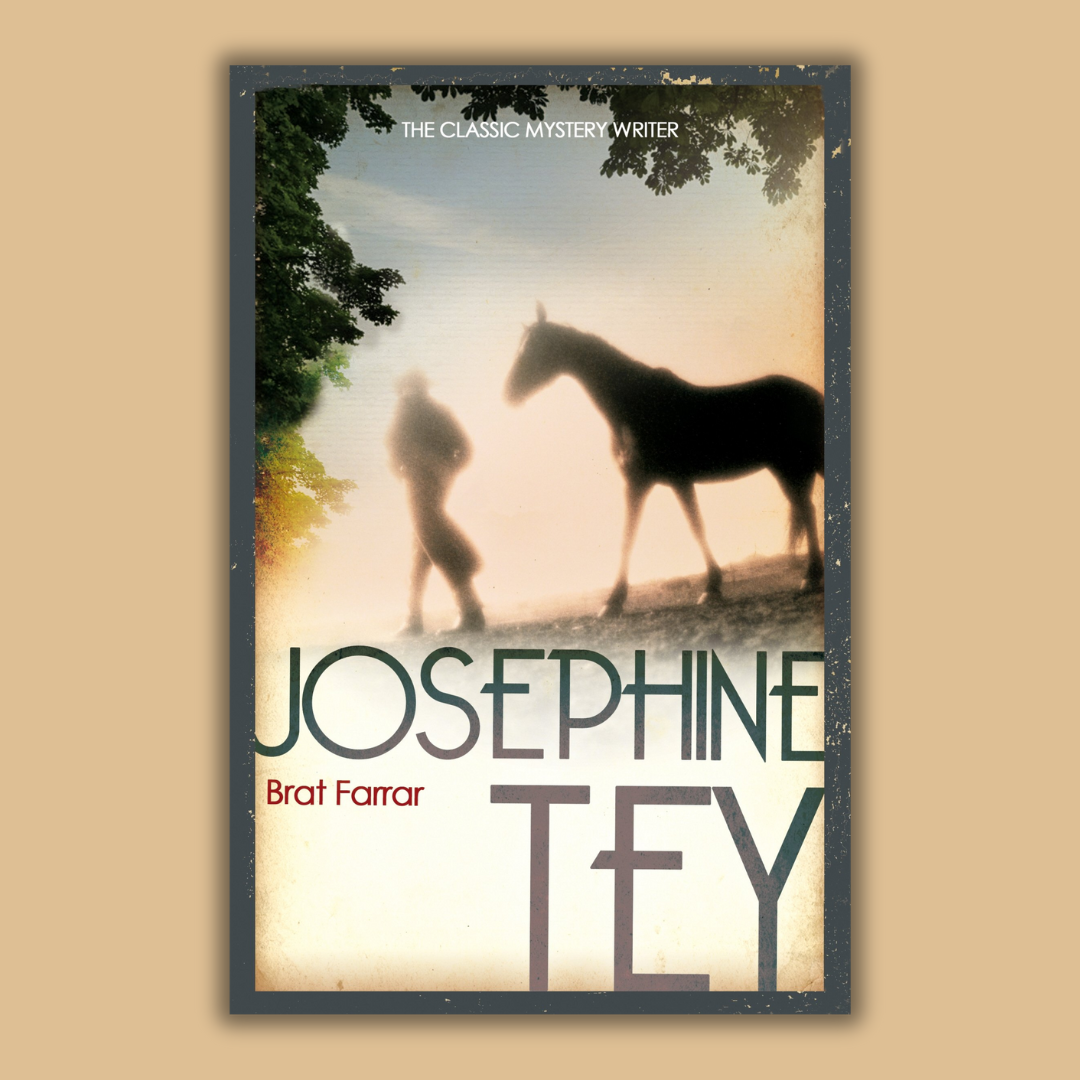

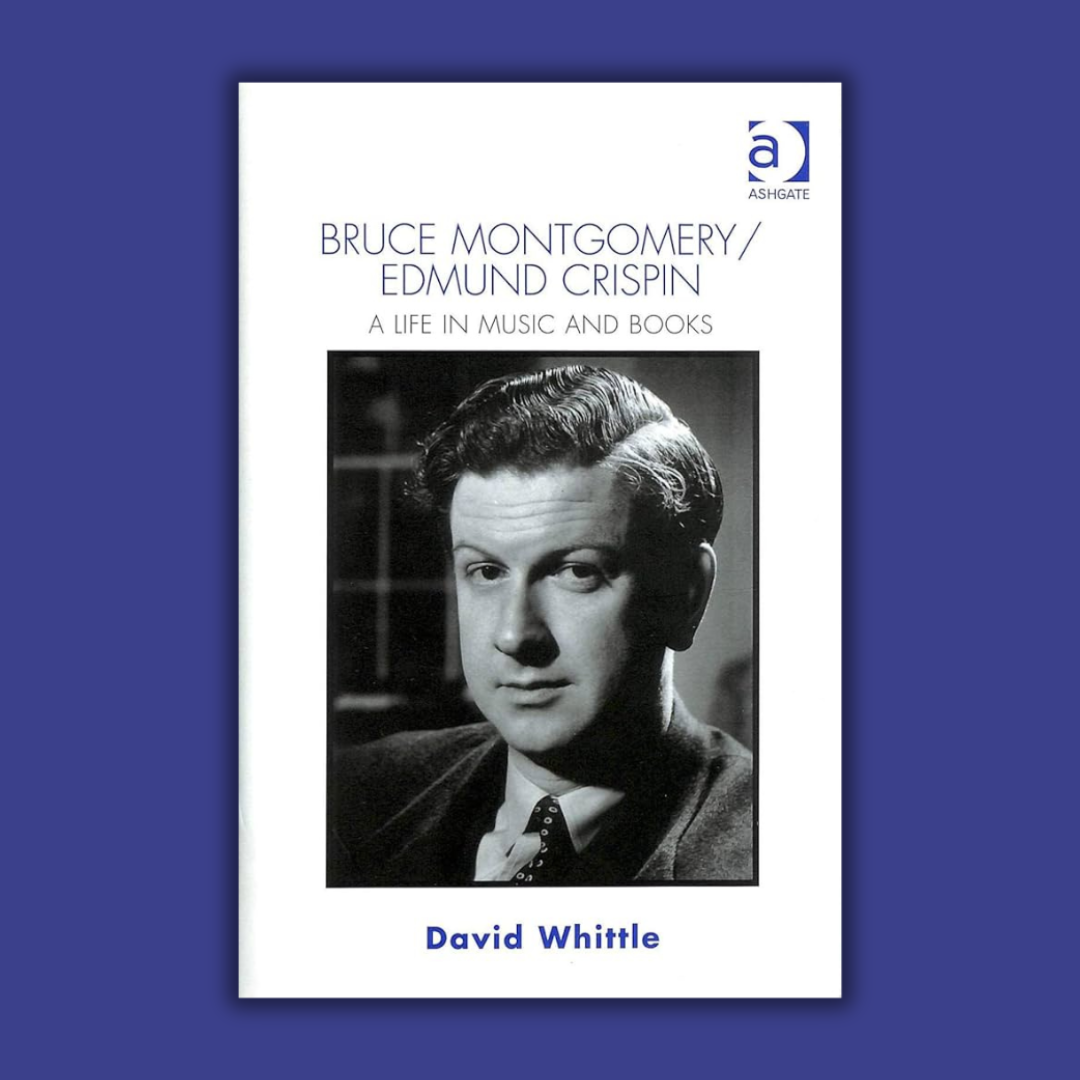

- Edmund Crispin (9 books)

- Christianna Brand (6 books)

- Anthony Gilbert (6 books)

- Approximately 65 per cent of my reading was done with physical books, 25 per cent via ebooks, and 10 per cent through audiobooks.

Analysis

- I'm pleased but not especially surprised by how much I read last year. I made some gradual changes (explained here) to how much I was using my phone and I replaced a lot of my mindless scrolling with reading, both by carrying a physical book with me everywhere and by using reading apps on my phone. I don't have the data for this, but I think I picked up the pace through the year as my new habits began to stick and I stopped using Instagram. I remember starting to have the feeling around midsummer that I was excited to finish whatever I was doing so I could get back to reading, which was something I hadn't felt since 2020.

- The fiction/non-fiction breakdown is a shock. I do look at a lot of non-fiction books for work, but I didn't realise I was reading so few of them cover to cover for pleasure. This feels especially galling given that I have written two non-fiction books myself, and would like to write more.

- Given my overwhelming preference for fiction throughout this year, it makes sense that I was reading crime more than anything else. There's a reason why I have a podcast dedicated to this genre — I do really like it. And I've long had a romance-reading habit for when I want to relax completely. For fantasy to be registering so highly is slightly startling, but it was a very distant third.

- My three top authors were all ones that I undertook to read as much of their work in full as possible so I could make a specific type of podcast episode about them. I wrote a little more about this in my November reading update. I'm pleased I did what I set out to do in this regard, but I'll be scaling it back in the future.

- I have no particular thoughts about the different formats, although I suspect my audio percentage will be higher for 2025 because I've been replacing podcasts with audiobooks recently.

The Best Books I Read in 2024

My ten favourite titles break down like this:

- nine fiction, one non-fiction

- nine originally in English, one translated from Japanese

- of the ten, there are

- two genuine "golden age" detective novels (from the interwar period or very close to it)

- two crime novels published in the 2020s, one historical and one contemporary

- two YA novels (although that term didn't exist when Noel Streatfeild was writing, of course)

- one more "literary" novel

- one fantasy novel

- and one memoir

The Vanishing Corpse by Anthony Gilbert

I read this while making the aforementioned podcast episode about Lucy Malleson aka Anthony Gilbert, and it ended up being one of my favourite golden age crime novels of the year. It even inspired another podcast episode, all about the trope it contains. First published in 1941, it follows the fortunes of an elderly spinster who rents a very isolated cottage, Lolly Willowes-style, thinking that she wants to end her days there. She arrives on a dark and snowy night to find that a dead body is already occupying the cottage, but when she brings the police back to inspect the corpse, it has vanished... I found it creepy and puzzling.

A Novel Disguise by Samantha Larsen

I read this historical novel thanks to a recommendation from my podcast production assistant Leandra. Set in 1784, it concerns the adventures of one Tiffany Woodall, half-sister of a librarian at an aristocratic country house. When said half-brother unexpectedly dies, she secretly buries him in the garden and dons a male disguise so she can go to his job in his place — initially for the money, but later because she becomes too intrigued by what is going on in the Big House to stop her subterfuge. I appreciated that the author had thoroughly researched her period and location, even including an appendix explaining the historical sources and secondary texts upon which she was drawing.

Black Plumes by Margery Allingham

This is one of two books in my top ten that I read because they were selected by the Shedunnit Book Club, which to me is confirmation that book clubs are a force for good in the world. Although Allingham is best known for her long series of novels featuring sleuth Albert Campion, this is a standalone from 1940 about an upper-class family in London who have owned and operated a prestigious art gallery for generations. It's a murder mystery, but it also has a fake engagement subplot (a favourite from my romance reading) and some very astute observations about generational differences between the 19th and 20th centuries. And a detective from Orkney! Tailor-made for me.

A Marvellous Light by Freya Marske

A queer romance set in an alternate version of Edwardian England where magic is real. It felt to me like a close cousin of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, although — full disclosure — I never actually finished reading that book because I had to return it to the library before I was done. I am very picky about my magic systems and this one satisfied all of my requirements, as well as being a well-written and well-paced adventure story. This is the first of a trilogy and I did read the other two books as well, but neither lived up to the pleasure of the first.

Tokyo Express by Seichō Matsumoto

This was the second book I read because of the Shedunnit Book Club and I liked it so much that I made a bonus episode where I interviewed the translator of the edition I read, Jesse Kirkwood. The novel was originally published in Japan in 1958 and I loved the social history it captures, from the professional etiquette of the police characters to the references to an earlier code of ethics. As the title indicates, the story is primarily about trains. The mystery definitely hails from the "humdrum" school of forensic alibi-breaking with much scrutiny of who was exactly where and when. Usually, I find this less appealing than the more psychology-driven kind of story, but I think this book and a few others have started to change my mind. I found the doggedness of the central detective oddly restful to read about.

Death at Morning House by Maureen Johnson

I had Maureen as a guest on Shedunnit when she was still working on her Stevie Bell novels, which are contemporary-set YA mysteries with a strong hint of 1920s true crime to them (the first being Truly Devious). She kindly sent me a proof copy of this new standalone that involves a 2020s teenager going to live on a tiny island for the summer to be a tour guide for a historic house. They end up uncovering the solution both to a recent crime as well as one that occurred during the Prohibition era. Real page-turning stuff and so well crafted. I read it in two sittings.

Marking Time by Elizabeth Jane Howard

I read three of the five volumes of Howard's Cazalet Chronicles in 2024 and this was by far my favourite. It covers the opening years of WW2, following the fortunes of the Cazalet daughters who were on the cusp of their independent lives when war hit — Louise, Polly, Clary, Nora — and what happens to them instead. Louise's sections are particularly heart-breaking, but the whole thing is so evocative and redolent with suppressed emotion that I still think about it regularly.

A Vicarage Family by Noel Streatfeild

This novel is Streatfeild's thinly-veiled autobiography about her childhood in an Edwardian vicarage. As she explains in the foreword, Vicky, the middle daughter of three children, is her character. She is relentlessly and unfavourably compared by all the adults around her to her artistic invalid older sister and her beautiful, charismatic younger sister. I'd like to think that today some kind teacher or relative would notice that Vicky is starved of love and possibly neurodivergent, but of course there is no such help for her here. I cried when I finished this book, because Noel so clearly succeeded in creating the life she wanted because of all the talents her family refused to recognise in her, and yet because she published this in 1963 when she was 68, I don't think she ever quite got over the way she was treated. And nor should she.

A Radical Romance by Alison Light

The only non-fiction book to make my top ten and possibly the best and most touching memoir I've ever read. I was already a fan of Light's writing because of Common People and Forever England but I'm now a lifelong devotee. A Radical Romance tells the story of her relationship with the historian Raphael Samuel, to whom she was married from 1987 until his death in 1996. He was 20 years older than she was and had lived a completely different kind of life to any that she had known to date, and yet they fit together. From her account, I think they were the living embodiment of what Peter Wimsey means in Gaudy Night when he says: "Anybody can have the harmony, if they will leave us the counterpoint." I cried when I finished this one too. There are many excellent sentences in it I could quote, but I'll just give you this one:

"A person is a crowd as well as an individual and comes not only with a history but with a thickly wooded present and a future lit by hopes and desires."

The Appeal by Janice Hallett

I loved this mystery that is set in an amateur dramatic society and told through emails and messages when I first read it. I stayed up and finished it in a single night, and thought it was wonderful that a bestselling crime writer in the 2020s was reviving the "documents in the case" format that Dorothy L. Sayers had used in 1930. I still think this book is good, which is why I've put it on this list, but the shine has been somewhat taken off for me since by reading Hallett's subsequent books, which all employ the same format to much less success.

Changes for 2025

This is the first time I've been thorough about tracking my reading and reflecting on the results, and been very clear with myself when I'm reading for work and when I'm reading for leisure. I have some ideas based on what I've learned.

Keep Reading

Setting out to read 104 books worked well for me in 2024, so I'm going to stretch myself a little further and aim for 120 this year. Averaging ten books a month feels doable. I like the "pace" feature on the Storygraph which tells you how far ahead or behind your goal you are, so I'll be keeping that on for motivation again. If you would like to follow along in real time, you can see what I'm reading at any given moment on my profile there. Do send me a friend request if you track your reading there too.

Seek Greater Variety

If last year showed me anything, it is that my problem finishing books is now in the past. I completed two books a week without difficulty. But looking through the list of everything I read, it still looks defensive to me, as if I was worried that if I strayed beyond the genres and styles that I was certain to find easy and comforting, I would find myself back in 2020's headspace again. I think that's why I read so little non-fiction and almost no literary or experimental fiction. It was crime fiction, romance, fantasy and YA that helped me recover my ability to read at length again so that's where I stayed, even after it was entirely necessary.

I'm never going to be someone who reads classic and literary fiction all of the time. I like a balanced reading diet. But I used to be someone who read it some of the time, and I'd like to explore that option again. The same goes for non-fiction. Thus, my goal is to read one non-fiction book and one work of literary, classic or experimental fiction a month. I feel most excited about this one, as if I'm opening a door again that has been closed for years. Still reading a lot, but differently. That feels right as my theme for 2025.

Stop Buying New Physical Books

A member of the Shedunnit Book Club recently introduced me to an acronym that is popular in the fibre arts community: SABLE, which means "Stash Acquired Beyond Life Expectancy". This applies to me and physical books — there are probably more in my house right now than I could read with the years left to me even if I had nothing else to do with my time. I'm not going to put myself on a complete book-buying ban, but I'm going to try harder not to bring new physical books into the house. If I want to support a writer with a pre-order, I'll do that with the ebook or audiobook edition, or put the title on hold at the library. I'm a member of three libraries including the London Library, so I'm not short of options to acquire older books to read in a non-permanent way.

Explore Other Forms

I didn't read a single book of poetry, novella, short story collection or play in 2024. That isn't unusual, though, because I've never been much of a reader of these forms (unless you count Sherlock Holmes short stories, I suppose). I'd like to try them out, though, so in the spirit of expanding my literary horizons I'm aiming to read four books this year that are in a form other than the novel.

Links to Blackwell's are affiliate links, meaning that I receive a small commission when you purchase a book there (the price remains the same for you). Blackwell’s is a UK bookseller that ships internationally at no extra charge.

Filed under: Reading Updates, Blog